Navigating virtual healthcare: Current evidence around migraine and telemedicine

Stay-at-home measures and safety concerns during the COVID-19 pandemic has greatly accelerated the global implementation of virtual healthcare—or telemedicine—which includes the use of phone and video visits, messaging, and wearable devices.1 In fact, at the University of California Los Angeles (UCLA) Health, CA, USA, virtual visits increased from <1% to 55% from March to April of 2020, leveling off at around 25% of all visits by the end of the calendar year.1 Telemedicine has not only shown promise in facilitating ongoing care for patients, but also in streamlining internal communications and external collaborations for healthcare professionals (HCPs) all over the world.2 Insurance and reimbursement policies are slowly becoming more accommodating globally,2 suggesting telemedicine is here to stay as a part of the “new normal” throughout the post-pandemic world.1

Telemedicine as a tool

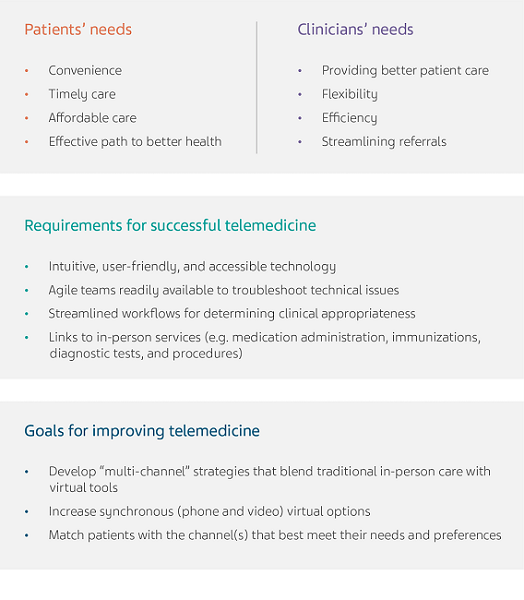

The European Commission (EC) defines telemedicine as “the provision of healthcare services, through the use of information and communications technology, in situations where the HCP and the patient (or two HCPs) are not in the same location. It involves secure transmission of medical data and information through text, sound, images or other forms needed for preventive care, diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up of patients.”3 It is important to recognize that telemedicine is not a new type of medical care, but a set of tools to aid successful and impactful healthcare from a distance—if and when it is appropriate, for a suitable subset of patients.4 Telemedicine can be provided synchronously (e.g. phone or video calls, real-time messaging) or asynchronously (e.g. email consultations),5 and can be tailored flexibly in a personalized manner depending on the individual patient’s conditions, needs, and the level of in-person care available to them.2 Figure 1 summarizes the patients’ and clinicians’ needs that telemedicine can address, along with requirements to achieve key goals.

Figure 1. Current needs to address and goals for telemedicine.2

Even before the rise of the COVID-19 pandemic, telemedicine was already becoming a viable tool across the medical field.6 A systematic review and meta-analysis examining studies on patients with diabetes found that virtual interventions (including phone calls, internet blood glucose monitoring systems, and automatic transmission of self-monitoring blood glucose using mobile phones) resulted in a small but significant improvement in hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) levels compared with traditional care.7 In the case of heart failure, a randomized and controlled trial found that when used in a well-defined population of patients with heart failure, remote patient management could reduce the percentage of days lost due to unplanned cardiovascular hospital admissions and all-cause mortality.8

To facilitate virtual networks not only for patients but also for communication between HCPs, the EC is currently supporting various digital health and care initiatives, including the virtual European Reference Networks (ERNs) for physicians to discuss and share knowledge about complex conditions virtually. Medical institutions around the world are proposing triage protocols to integrate such networks more efficiently and systematically into their everyday clinical workflows to provide the best care for their patients, whether it be virtual, in-person, or both.1

Advantages and challenges of telemedicine

ADVANTAGES

One of the major advantages of telemedicine is that patients generally report a positive experience, including convenience and flexibility.2 Additionally, telemedicine allows physicians to reach into new or previously difficult-to-reach geographic regions to increase healthcare access for many patients.2 For instance, when the University of California San Francisco, CA, USA implemented an e-consultation program, the proportion of patients who received specialty care increased by 17% within 2 weeks.9 Finally, telemedicine may reduce costs and improve outcomes, though additional systematic studies are still necessary.10

CHALLENGES

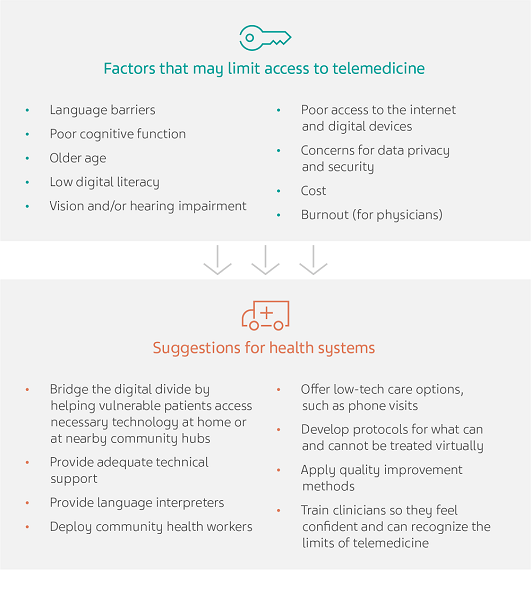

Of the several challenges that come with adopting new platforms, a major concern is determining the clinical appropriateness of telemedicine—namely, when and how to decide whether a virtual or in-person visit would be more suited.1 Additional challenges include patients skipping care,1 or even overusing virtual care due to its convenience.2 Importantly, the lack of access and technological support for key patient populations, some of which are summarized in Figure 2, are serious and ongoing issues.2 The lack of validation of technology is also commonly reported by patients as a barrier to using digital health tools.11 Reduced access to broadband services in rural areas also causes disparity in telemedicine6— such “red flags” should be considered by physicians on a case-by-case basis.1

Figure 2. Challenges to telemedicine and suggested solutions.2

Telemedicine for headache and migraine

For headache care, the European Headache Federation (EHF) provides an e-consultation system mainly for obtaining second opinions.12 Although the use of telemedicine is still in its infancy in headache medicine,13 a 2020 survey among primary care physicians at UCLA identified that headache and migraine were among the most appropriate conditions for the use of virtual visits, supporting the possibility of its wider implementation in the field.1

TELEMEDICINE FOR HEADACHE DISORDERS BEFORE THE COVID-19 PANDEMIC

The value of telemedicine for headache had been documented in a study in 2017, in which patients from Norway referred with non-acute headaches for specialist consultation at Tromsø University Hospital, Tromsø, Norway were randomized to telemedicine or traditional visits.14 After 3 months, patient satisfaction and treatment compliance were similar, and improvement from baseline was reported equally between both groups.14 Another randomized trial on telemedicine showed that over one year of monitoring patients living with migraine, clinical outcomes (e.g. improvement in disability associated with migraine, number of headache days, and headache severity) were no different between those in the telemedicine and in-person visit groups.15 Moreover, convenience was rated higher and visit times were shorter in the group receiving virtual care, compared with the group visiting in-person.15 If appropriately triaged and communications are optimized, e-consultations could present value in headache medicine.13

INCREASED TELEMEDICINE IN HEADACHE CARE DURING LOCKDOWN

In the initial months during the global spread of the COVID-19 pandemic, strict quarantine measures contributed to a marked increase in telemedicine use.1 During this time, patients in the observational Italian Headache Registry (Registro Italiano Cefalee, RICE, Italy) showed a mild improvement of migraine features, leading authors to suggest that patients may favor follow-ups via virtual visits, diaries, and frequent remote contacts.16 A study in the Netherlands also reported that an “intelligent lockdown” led to a decrease in monthly migraine days and days of acute medication use for patients living with migraine, and that headache e-diaries were an effective virtual tool that can be used in clinical practice and research.17

When the Hawaii Pacific Neuroscience (HPN) Institute, Hawaii, USA, surveyed their patients during lockdown, telemedicine was found to be well received by patients living with or without migraine.18 A majority of surveyed patients found telemedicine to be easy to use and as valuable as an in-person visit, and patients living with migraine were more likely to report that they would have missed their medical appointments without the virtual option compared with patients without migraine (37/68 [54.4%] vs. 56/144 [38.6%]).18 Further, a majority of surveyed patients reported to prefer or consider telemedicine for future appointments over in-person visits.18

When 51 children and adolescents with migraine were provided telemedicine during lockdown between March and June of 2020 at the Pediatric Neurology Division of the All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Rishikesh, India, physicians were able to identify and advise on significant clinical events, drug-related adverse effects, systemic complaints, worsening headache, and changes in medication dose or type.19 Importantly, around 90% of the patients’ caregivers reported to be satisfied with the quality of teleconsultation, suggesting virtual care was a feasible and efficacious option for young patients with migraine.19

Considerations and next steps to deliver high-quality telemedicine

Though telemedicine shows promise, there is a need for careful consideration of how best to position this new platform going forward.6 Effective telemedicine requires a trusting relationship between the patient and clinician, and further research is needed to understand which patient populations are best suited for telemedicine, the clinical outcomes of telemedicine, and how to best provide evidence-based guidance for physicians on its implementation.6 As virtual care is here to stay for the long-term, healthcare systems should continue to build virtual solutions to improve care and access for a broader patient population.2

Croymans D, Hurst I, Han M. Telehealth: The Right Care, at the Right Time, via the Right Medium. NEJM Catalyst Innovations in Care Delivery 2020. Available from: https://catalyst.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/CAT.20.0564. Accessed: 2021 Feb 23.

Dorn SD. Backslide or forward progress? Virtual care at U.S. healthcare systems beyond the COVID-19 pandemic. NPJ Digit Med 2021;4(1):6.

Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions on telemedicine for the benefit of patients, healthcare systems and society. Available from: http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/ALL/?uri=CELEX:52008DC0689. Accessed: 2021 Feb 25.

Hollander JE, Sites FD. The Transition from Reimagining to Recreating Health Care Is Now. NEJM Catalyst Innovations in Care Delivery 2020. Available from: https://catalyst.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/cat.20.0093. Accessed: 2021 Feb 24.

Mold F, Cooke D, Ip A, Roy P, Denton S, Armes J. COVID-19 and beyond: virtual consultations in primary care—reflecting on the evidence base for implementation and ensuring reach: commentary article. BMJ Health Care Inform 2021. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7804830/. Accessed: 2021 Feb 24.

Hodgkins M, Barron M, Jevaji S, Lloyd S. Physician requirements for adoption of telehealth following the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. NPJ Digit Med 2021;4(1):19.

Lee PA, Greenfield G, Pappas Y. The impact of telehealth remote patient monitoring on glycemic control in type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of systematic reviews of randomised controlled trials. BMC Health Serv Res 2018;18(1):495

Koehler F, Koehler K, Deckwart O, et al. Efficacy of telemedical interventional management in patients with heart failure (TIM-HF2): a randomised, controlled, parallel-group, unmasked trial. Lancet 2018;392(10152):1047–57.

Gleason N, Prasad PA, Ackerman S, et al. Adoption and impact of an eConsult system in a fee-for-service setting. Healthc (Amst) 2017;5(1–2):40–5.

Totten AM, Hansen RN, Wagner J, et al. Telehealth for Acute and Chronic Care Consultations. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2019. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK547239/. Accessed: 2021 Feb 24.

Palacholla RS, Fischer N, Coleman A, et al. Provider- and Patient-Related Barriers to and Facilitators of Digital Health Technology Adoption for Hypertension Management: Scoping Review. JMIR Cardio 2019;3(1):e11951.

Pereira-Monteiro J, Wysocka-Bakowska M-M, Katsarava Z, Antonaci F. Guidelines for telematic second opinion consultation on headaches in Europe: on behalf of the European Headache Federation (EHF). J Headache Pain 2010;11(4):345–8.

Robblee J, Starling AJ. E-Consultation in Headache Medicine: A Quality Improvement Pilot Study. Headache 2020;60(10):2192–201.

Müller KI, Alstadhaug KB, Bekkelund SI. Telemedicine in the management of non-acute headaches: A prospective, open-labelled non-inferiority, randomised clinical trial. Cephalalgia 2017;37(9):855–63.

Friedman DI, Rajan B, Seidmann A. A randomized trial of telemedicine for migraine management. Cephalalgia 2019;39(12):1577–85.

Delussi M, Gentile E, Coppola G, et al. Investigating the Effects of COVID-19 Quarantine in Migraine: An Observational Cross-Sectional Study From the Italian National Headache Registry (RICe). Front Neurol 2020;11:597881.

Verhagen IE, van Casteren DS, Lentsch S de V, Terwindt GM. Effect of lockdown during COVID-19 on migraine: A longitudinal cohort study. Cephalalgia 2021;333102420981739.

Smith M, Nakamoto M, Crocker J, et al. Early impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on outpatient migraine care in Hawaii: Results of a quality improvement survey. Headache 2020.

Sharawat IK, Panda PK. Caregiver Satisfaction and Effectiveness of Teleconsultation in Children and Adolescents With Migraine During the Ongoing COVID-19 Pandemic. J Child Neurol 2021;36(4):296–303.