Comorbidities: The added burden of migraine

Many studies have found that migraine occurs with comorbidities like anxiety, depression, and pain at a greater coincidental rate in migraineurs than in the general population.1 Though migraine comorbidities can complicate diagnosis and treatment, they can also provide insight into the pathophysiology of migraine.1

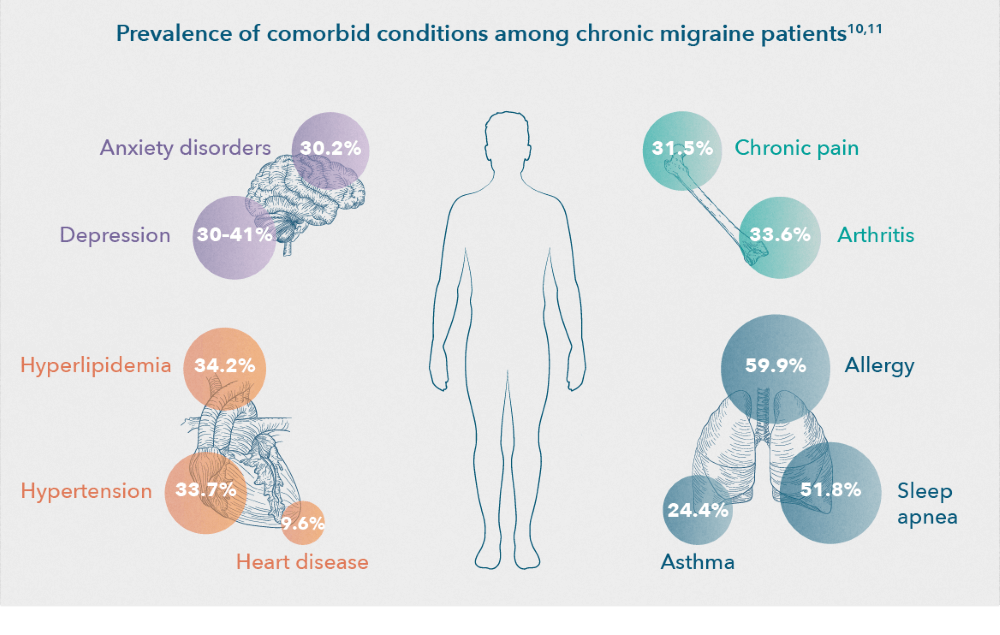

Nearly 88% of chronic migraine patients have at least one comorbid condition, while 39% of chronic migraine patients have four or more comorbid conditions.2 The most common migraine–related comorbidities were characterized by The Chronic Migraine Epidemiology and Outcomes (CaMEO) study into the subgroups of pain, psychiatric, cardiovascular and respiratory diseases,3 although many others are also prevalent (i.e., obesity, sleep disorders, and epilepsy).4–9

The most common comorbidities associated with migraine

PSYCHIATRIC COMORBIDITIES

One of the most common comorbidities with migraine is a wide range of psychiatric disorders.8,12 About 37% of chronic migraine patients have a mental disorder, with the most common ones being depression, bipolar disorder, and anxiety.2 Furthermore, patients with a combination of anxiety disorders and major depression are more likely to have migraine compared with those who have only depression or anxiety.13,14 Psychiatric comorbidities tend to increase the risk of developing chronic migraine, decrease the quality of life of patients with migraine, and complicate migraine management.8 These elements outline how essential it is to screen patients with migraine for psychiatric comorbidities.8

Anxiety

Approximately 19–30% of chronic migraine patients have an anxiety disorder.2,10 Among the anxiety disorders, generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD), and panic disorder (PD) are the most strongly linked with migraine.8 Controlling the anxiety of patients with migraine is associated with improved quality of life, adherence to a migraine treatment plan, and effectiveness of migraine treatment.8

Depression

Studies found that migraineurs are over 2.5 times more likely to suffer from depression compared with non-migraineurs.8 The association between migraine and major depressive disorder (MDD) is even stronger for patients with chronic migraine and for patients who have migraine with aura.8 Current research aims to identify molecular mechanisms that may underlie headache when neurons are stressed due to depression.15 Although there is no current evidence that improved control of depression helps to control migraines, it is important to identify and treat depression in patients with migraine because it is a significant predictor of migraine chronification.8

CHRONIC PAIN

Migraine is comorbid with a large number of pain disorders, including arthritis and noncephalic pain.6,16 Despite pain disorders being more common in chronic migraine than in episodic migraine, this is not well studied.16

Arthritis

Severe headache pain is associated with an increased risk of arthritis, osteoarthritis, and rheumatoid arthritis.6 About one-third of chronic migraine patients have arthritis.10 Risk of arthritis also increases with increasing migraine frequency.6

Noncephalic pain

The CaMEO study found that noncephalic pain and migraine are significant comorbidities.16 In this study, noncephalic pain was common in people with migraine, regardless of migraine frequency.16 Although further studies are required, noncephalic pain is a suggested marker for headache chronicity that could identify people with episodic migraine who are at risk of chronic migraine, and people with chronic migraine at risk of persistent chronic migraine.16

CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASE

Heart-related comorbidities are also common among chronic migraine patients,2 with cardiovascular disorders more often associated with chronic migraine than with episodic migraine.10 More specifically, severe headache pain, a symptom more common in chronic migraine,17 is associated with increased risk of peripheral artery disease, hypertension, and high cholesterol.6 34% of chronic migraine patients are diagnosed with hypertension, 34% with hyperlipidemia, and 9.6% with coronary heart disease.10

RESPIRATORY COMORBIDITIES

Increasing monthly headache day (MHD) frequency is associated with increased risk for asthma and allergy/hay fever.6 A population-based cohort study of 6,647 adult patients showed that there is an increased risk of asthma in patients with migraine and that comorbid asthma was associated with increased risk of new onset chronic migraine.6

ADDITIONAL COMORBIDITIES ASSOCIATED WITH MIGRAINE

Alongside the most common comorbidities discussed above, chronic migraine patients typically have multiple additional chronic comorbid conditionssuch as obesity, sleeping disorders, and neurological disorders such as epilepsy.4–9

Obesity

Obesity may enhance the frequency and severity of headache attacks and appears to increase the risk for having migraine.4 In a laboratory study in rats, diet-induced obesity led to the sensitization of meningeal trigeminovascular afferents.4 This resulted in the enhancement of the nociceptive pathway and suggests a mechanism for enhanced headache susceptibility in obese individuals.4 Meanwhile in the clinic, a longitudinal population study identified that among individuals with episodic headache, obesity was associated with a five-fold increase of annual incidence of new‑onset chronic daily headaches (CDH).5 Another study also suggested that obesity is associated with the frequency and severity of migraine attacks.5 Furthermore, CDH prevalence increases with shifts in BMI category from normal to overweight, obese, and morbidly obese, respectively.5 Therefore, obese patients with migraine may have more frequent and severe attacks and may be more likely to develop central sensitization.5

Sleep disorders

Sleep disorders are more prevalent in patients with migraine than in the general population.8 Migraine is associated with a wide variety of sleep disorders, such as restless leg syndrome, parasomnias, sleep apnea, and insomnia.8 For example, severe headache pain is associated with an increased risk for insomnia,6 and chronic short sleep is associated with more severe headaches.8 Results of a large cross-sectional population study showed that the prevalence of poor sleep quality was significantly higher among those with migraine than among those without.6 These results suggest that migraine and sleep problems have a common underlying pathophysiology.7 Furthermore, a small, randomized, placebo-controlled trial showed significant improvement in headache frequency and severity, and even a reversal from chronic migraine to episodic migraine in patients who underwent behavioral sleep modification compared with a placebo intervention.8 The neurobiological mechanism underlying the bidirectional relationship between migraines and sleep is likely due to some overlapping pathophysiology and shared anatomical structures within the brain.8

Epilepsy

Migraine and epilepsy are linked by their symptom profiles, comorbidity, and treatment.9 Individuals with epilepsy are 2.4 times more likely to develop migraine than their relatives without epilepsy.18 Although migraine is common in patients with epilepsy and epilepsy is less common in migraine sufferers, the presence of one of these disorders increases the likelihood of the other. The comorbidity of migraine and epilepsy may be explained by a state of neuronal hyperexcitability that increases the risk of both disorders.18 When both diagnoses occur together, therapy with agents effective for both conditions should be considered.18

Identifying comorbidities in migraine patients is essential to diagnosis and treatment

Understanding comorbidities of migraine is important for managing the disease.6 However, further work is required to clarify the causal sequence of relationships, the potentially confounding role of migraine treatment, and shared risk factors.6

Wang SJ, Chen PK, Fuh JL. Comorbidities of migraine. Front Neur 2010;1(16).

Thorpe KE. Prevalence, Health Care Spending and Comorbidities Associated with Chronic Migraine Patients. 2017;15.

R. B. Lipton, Fanning KM, Buse DC, et al. Identifying natural subgroups of migraine based on comorbidity and concomitant condition profiles: results of the Chronic Migraine Epidemiology and Outcomes (CaMEO) study. Headache: The Journal of Head and Face Pain 2018;58(7):933–947.

Marics B, Peitl B, Varga A, et al. Diet-induced obesity alters dural CGRP release and potentiates TRPA1-mediated trigeminovascular responses. Cephalalgia 2017;37(6):581–91.

Bigal ME, Lipton RB. Obesity is a risk factor for transformed migraine but not chronic tension-type headache. Neurology 2006;67(2):252–7.

Buse DC, Reed ML, Fanning KM, et al. Comorbid and co-occurring conditions in migraine and associated risk of increasing headache pain intensity and headache frequency: results of the migraine in America symptoms and treatment (MAST) study. J Headache Pain 2020;21(1):23.

Vgontzas A, Pavlović JM. Sleep Disorders and Migraine: Review of Literature and Potential Pathophysiology Mechanisms. Headache: The Journal of Head and Face Pain 2018;58(7):1030–9.

Minen MT, Begasse De Dhaem O, Kroon Van Diest A, et al. Migraine and its psychiatric comorbidities. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2016;87(7):741–9.

Bigal ME, Lipton RB, Cohen J, Silberstein SD. Epilepsy and migraine. Epilepsy & Behavior 2003;4:13–24.

Buse DC, Manack A, Serrano D, Turkel C, Lipton RB. Sociodemographic and comorbidity profiles of chronic migraine and episodic migraine sufferers. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry 2010;81(4):428–32.

Buse DC, Rains JC, Pavlovic JM, et al. Sleep Disorders Among People With Migraine: Results From the Chronic Migraine Epidemiology and Outcomes (CaMEO) Study: Sleep Disorders Among People With Migraine. Headache 2019;59(1):32–45.

Antonaci F, Nappi G, Galli F, Manzoni GC, Calabresi P, Costa A. Migraine and psychiatric comorbidity: a review of clinical findings. J Headache Pain 2011;12(2):115–25.

Mongini F, Rota E, Deregibus A, et al. Accompanying symptoms and psychiatric comorbidity in migraine and tension-type headache patients. Journal of Psychosomatic Research 2006;61(4):447–51.

Merikangas KR. Migraine and Psychopathology: Results of the Zurich Cohort Study of Young Adults. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1990;47(9):849.

Karatas H, Erdener SE, Gursoy-Ozdemir Y, et al. Spreading Depression Triggers Headache by Activating Neuronal Panx1 Channels. Science 2013;339(6123):1092–5.

Scher AI, Buse DC, Fanning KM, et al. Comorbid pain and migraine chronicity: The Chronic Migraine Epidemiology and Outcomes Study. Neurology 2017;89(5):461–8.

Katsarava Z, Buse DC, Manack AN, Lipton RB. Defining the Differences Between Episodic Migraine and Chronic Migraine. Curr Pain Headache Rep 2012;16(1):86–92.

Lipton RB. Comorbidity of migraine: the connection between migraine and epilepsy. Neurology 1994;44(10 Suppl 7):S28–32.